The development of Central and Eastern European economies over the past few decades is truly a remarkable achievement. The ten CEE countries analyzed in this report—Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia—increased per capita GDP by 115 percent in the period 2004–2019.1 In 2019, the market openness of these Digital Challengers, as we call them, reached 123 percent2 and the average unemployment rate across the region was the lowest in recent history, at just 4.6 percent. Productivity increased to €36 per hour worked in 2019 and is catching up with the levels seen in Western Europe.

Digital Challengers in the next normal

The success of CEE was largely driven by strong traditional sectors of the economy, dynamic exports, investments from abroad, labor-cost advantages and funding from the European Union (EU). However, many of these engines are now gradually powering down. Moreover, it is clear that CEE is still vastly undercapitalized. With labor capacity at its limit and strong dependence on exports, there is little more that the region can do with its historical growth engines.

The pace of digitization increased slightly, but COVID-19 is accelerating changes

In our 2018 report The rise of Digital Challengers, we suggested that digitization was the new lever that CEE countries could use to stay on their growth trajectory. Our analysis showed that CEE can gain significant economic benefits from digitization, primarily due to productivity gains. According to our calculations, closing the gap to Western and Northern Europe had the potential to add as much as €200 billion in additional GDP by 2025.

In this report we take the opportunity to assess the progress of CEE countries (Exhibit 1). With the digital economy reaching €94 billion in 2019, it is clear that CEE exceeded the “business as usual” scenario laid out in the previous report by €2 billion. But it was still €23 billion below the level of the aspirational scenario. This implies that the region has not yet managed to fully leverage digitization of the public and private sectors, and has failed to significantly boost e-commerce and offline consumer spending on digital equipment.

In 2017–2019, the digital economy in CEE grew by almost 8 percent a year, much higher than the pace of change in the largest five economies in Western Europe, or the “Big 5”—France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. However, the group we use as a primary reference in our reports—the Digital Frontrunners of Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden—managed to grow even faster, widening the gap with CEE even further.

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a global humanitarian crisis that has upended lives and cast a shadow of uncertainty over the future. There is one thing, however, we can be sure about: the world that emerges from the pandemic— or, as we call it, the next normal—will be more digital than today.

Would you like to learn more about McKinsey Digital?

This is reflected in our investigation into the digital economy. During the first months of the COVID-19 lockdowns, our estimates show that the digital economy in CEE accelerated, capturing 78 percent, or €5.3 billion, of the increase seen in the whole of 2019 within the space of just five months (Exhibit 2). The rate of growth from January to May 2020, at 14.2 percent, was almost twice as high as the year-on-year change observed in 2017–2019 (7.8 percent).

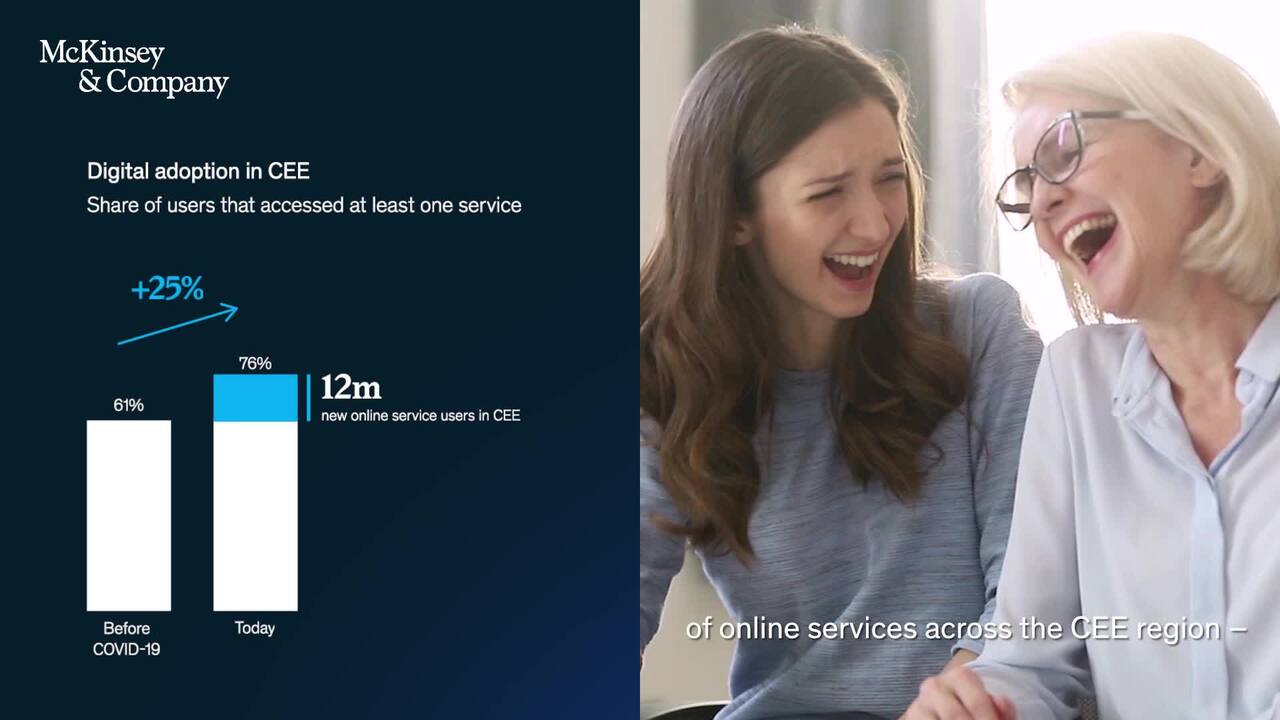

During the pandemic, the way people interact, work, travel, spend their leisure time, use public services and perform other routine activities has shifted dramatically. As the McKinsey COVID-19 Digital Sentiment Insights survey shows, almost 12 million new users of online services appeared in CEE—more than the population of Slovakia, Croatia and Slovenia put together (Exhibit 3). Notably, this increase was not only driven by the young population: the strongest growth was actually observed among consumers aged over 65. While it is difficult to judge the “stickiness” of those behaviors, around 70 percent of survey respondents declared they will continue using online services after the pandemic.

This leads us to another important point. Once consumers get used to new contactless channels, they might not be inclined to go back, particularly since health and safety measures related to COVID-19 may not disappear anytime soon. This unlocks great potential for companies that had already invested in digitization prior to the outbreak. But it also puts great pressure on other organizations, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which lag behind on digital adoption, to quickly transform the way they interact with customers and run their businesses.

COVID-19 has also impacted the labor market, with many people losing their jobs or being put on temporary furlough. While the full effect is not yet reflected in the numbers, this may soon change, particularly as many support programs and furlough schemes are coming to an end. According to new analysis by the McKinsey Global Institute, around 9.9 million jobs in CEE are at risk due to COVID-19.3 About 36 percent of these jobs are also at risk of displacement due to automation by 2030.4 This hints at the fact that COVID-19 may have accelerated changes that will lead to faster automation. Policymakers and businesses would be well advised to introduce programs for reskilling and upskilling in order to avoid structural unemployment in the future.

Restrictions imposed during the pandemic accelerated digital adoption by citizens and required companies and governments to adjust the way they interact with them. Many decision makers and businesses now see digitization as a necessary step forward.

CEE’s digital foundations are strong, but the talent pool needs strengthening

In our previous Digital Challengers report, we said that having a resilient economy, a strong talent pool, high-quality digital infrastructure, and a vibrant technology ecosystem was the basis for digitization to become CEE’s new growth engine. This time we once again looked at those aspects. Below, we describe what we found.

Macroeconomic performance

Since 2004, the gap between Digital Challengers and Digital Frontrunners in terms of GDP at purchasing power parity (PPP) has narrowed from 60 to 31 percent.5 While economic growth has been slowing down recently, it still remains more than three times as fast as the Big 5 and almost twice as fast as the Digital Frontrunners. Despite recent increases in costs, CEE’s labor also remains much more affordable: with current growth rates, it would take almost 18 years for Digital Challengers to reach the level of labor costs seen among Digital Frontrunners in 2019.6

Central and Eastern Europe needs a new engine for growth

Talent pool

While Poland and Slovenia topped the 2018 global PISA rankings for primary and secondary education, seven out of ten Digital Challenger countries scored below the EU average in math, science, and reading.7 During the peak of COVID-19, schools had to move to remote-education solutions, which uncovered significant gaps in digitization in this sector. Going forward, it would be advisable for the education system to put more emphasis on digital technologies—not only because of the threat of future lockdowns, but because, in general, the way children engage with information has changed considerably over the past decades.

In our earlier report we stated that the CEE region had the largest pool of STEM graduates in Europe. This is no longer the case, since the number of students graduating in these subjects fell from 234,000 in 2016 to 216,000 in 2018.8 Moreover, higher-education attainment remains lower than among Digital Frontrunners, with a 14-percentage-point gap between the two groups today.9 Going forward, attracting more students to STEM subjects by supporting university–industry collaborations could help strengthen the CEE talent pool.

One of CEE’s strongest assets is its people. The “brain drain,” or migration of the educated workforce, has been a major challenge for the region in the past. While this remains an important issue, another trend has now emerged. In 2018, CEE experienced positive net migration for the first time in 30 years,10 with migrants serving as a new source of talent.

Digital infrastructure

CEE continues to enjoy high-quality digital infrastructure. For instance, more than 92 percent of populated areas are covered by 4G, and the share of fiber-optic broadband has increased to 47 percent, overtaking the Big 5 and Digital Frontrunner countries. Moreover, connectivity is affordable in CEE. Looking ahead, the biggest source of competitiveness will be 5G technology, which enables real-time data analysis and the development of the Internet of Things (IoT). Current forecasts are that CEE will achieve only around 20 percent 5G penetration in 2024—less than half of the level of Digital Frontrunners and the Big 5.11

Tech ecosystem

CEE’s unicorns are worth around €31 billion.12 2019 marked yet another record year for technology investment in CEE, with almost €1.5 billion in venture capital attracted to the region.13 This is more than five times the level in 2015, and puts Digital Challengers ahead of the other two country groups in terms of growth of venture capital.14 However, CEE economies remain vastly underinvested: in the 2013–2020 period, investment per capita was eight times smaller than in the Big 5 and 13 times smaller than in Digital Frontrunners.15

Action needed by policymakers, business and individuals in the next normal

To move closer to the aspirational scenario for the digital economy outlined in our previous report, action is required by all stakeholders in Digital Challenger countries. Restrictions imposed during the pandemic are a catalyst for digital transformation. Not because they have significantly changed the solution, but because they have made the solution all the more important. Now, businesses need an e-commerce website, online customer service and cloud and automation technologies (including data analytics, AI, robotic process automation, and improved IT architecture) in order to survive. Therefore, many of the recommendations that we put forward in our report two years ago remain valid today. To successfully achieve a digital transformation, enterprises need a holistic approach, digitizing customer interactions, optimizing operations, and modernizing their IT.

Policymakers could consider bringing more public services online to meet the expectations of an increasingly digital society. Apart from developing internal capabilities, public institutions would be well advised to create a digital ecosystem in which individuals and businesses can thrive. They can do this by supporting entrepreneurship, creating incentives for SMEs to digitize and cooperating with “tech clusters”—sectors that enhance the competitiveness of the region.

What is also important is to boost collaboration on the CEE level. In this report we put forward the idea of creating a CEE Digital Council, similar to the initiative run by the Nordic states, that would drive the digital agenda and tap into the potential of a single digital market. Finally, digitization in the public sector should aim to improve digital inclusion and human development. To this end, governments could look into promoting digital skills among the population, on the one hand preparing younger generations for the demands of the future job market, and on the other helping adults to reskill or upskill.