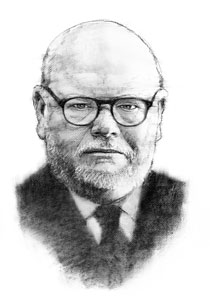

Britt Harris joined the University of Texas Investment Management Company (UTIMCO) as president, CEO, and CIO in August 2017, after leading the Teacher Retirement System of Texas (TRS) for more than a decade.

In that earlier stint, Harris was instrumental in developing what has become known in the industry as the Texas Way of institutional investing. Shortly after joining UTIMCO, Harris spoke with McKinsey’s Grant Birdwell and Bryce Klempner.

Fique em dia com seus tópicos favoritos

McKinsey: You’ve developed the so-called Texas Way of investing. How would you describe it?

Britt Harris: When I came back to Texas, I came from a big private fund. There, success was to beat your benchmarks, stay within your risk parameters, meet with the board once a year for half an hour, tell a couple of interesting stories about the markets, give your evaluation of the future, talk about a couple things you’re working on, and get out of there in 29 minutes. Many public funds, on the other hand, have six or eight board meetings a year that run for two days each. It was a big adjustment, and it points to a key component of the Texas Way. At its core, the Texas model is to go from robber baron to professional management. In the robber-baron era, say the 1940s, the board and the management of most enterprises were 90 percent the same people. In the robber-baron model, you hear people talk about “the staff.” It suggests, “We make the decisions. These people are our staff; they’ll do the research for us, but we have the ball.” I had never heard the term “staff” applied to a professional investment team until I came to a public fund.

After the 1940s, most organizations moved to a professional-management model, where the board says, “None of us have ever done this, so let’s hire somebody who knows how to do it.” For investment funds, the role of the board becomes to hire the CEO; give the CEO return objectives, risk parameters, and resources; and install an independent audit process. It’s an agency structure that is much more productive and stable and can produce better returns. Because the professional-management structure is so unusual in the US, you create a massive strategic advantage just by doing that.

With that professionalization come a lot of other desirable characteristics: respect for people, a culture that emphasizes the mission, stronger processes, deeper capabilities, and carefully cultivated relationships (see sidebar, “The Texas Way”).

McKinsey: The Texas Way has worked very well for you, but it’s not the only way. Many in the industry are attracted to the so-called Canadian model. How do you see the differences between the two?

Britt Harris: As I understand it, the Canadian model basically focuses on a few things. First, they are trying to bring investments in-house, getting rid of as many general partner (GP) relationships as they can. They’re basically creating an in-house investment bank, competing directly against other investors. So they’re attracting many, many people. The compensation is not that far off a bulge-bracket bank, but it’s a better job than at the big banks, in my view, because they have more control over what they’re doing, and they have a higher purpose. So I think about the Canadian model as focused on being competitive with global GPs, while the Texas model is more focused on being collaborative.

Second, some of them have such massively positive cash flow coming in over the next 20-plus years that they’re able to make commitments based on a fund size that’s much larger than their current size. You look at some of the commitments made to coinvestment in particular and think, “Who has this much money?” Every single transaction, it seems, they’re in there with $500 million. They’re able to do that because the probability that they’re going to be, say, two times their current size is very high, because of their funding source.

Finally, the Canadians have a completely different agency structure from the US, one that is not controlled by government in the same way. It’s really more of a professional-agency structure.

McKinsey: Your approach favors collaboration over competition, including in your relationships with external asset managers. You’re well known for having pioneered innovative strategic partnerships with fund managers. How do these work?

Britt Harris: Let me explain this in a roundabout way, using an anthropological theory I heard from the CEO of a large US bank. Imagine early pilgrims showing up at Plymouth Rock. Over time, some stayed in Boston, some went to Texas, and some went West. He said the problem Northerners have, and he counted himself in that number, is that they never had to worry too much about who people were, at least in terms of safety. So New Yorkers tend to lead with what they know. They come down South and start with, “I’m going to tell you how smart I am,” and they can’t figure out why they don’t get traction. Whereas the ones who went to Texas lived on the prairie in a little wooden hut with nobody for 100 miles in any direction. You can imagine in that context that when your little girl suddenly runs into the hut and says, “Daddy, there’s somebody on the butte,” you cared first and foremost about who that person was, not what they knew. For people down South, trust matters a lot more. We want to know who you are before we care about what you know. Once we’re convinced that you have high integrity and you have high character, then we’re all ears.

So again, the Texas model is collaborative rather than competitive. We select firms that we put on a “premier list” after we’ve fully vetted their character and their capabilities. Then we try to be one of their five most important customers—not just the largest, but the most committed, the most professional, and the easiest to do business with.

We don’t believe in one-night stands. We believe in long-term relationships—making commitments and sticking to them. That’s absolutely essential in terms of trust. I want to know that you’re going to be sitting in that exact same chair next year and two or three years from now. I don’t expect you to be perfect, but I don’t want to have to worry about you trying to sell me something just to get it off your books.

McKinsey: Many limited partners want to be their GPs’ favorite client. What do you have to do to get there?

Britt Harris: First, you have to pay your way. I always tell people that we don’t want something for nothing. We just want to get the value we’re requesting from what we’re paying, and I want our payment to be aligned. When I first started strategic partnerships back in 1994, I asked, “What does it take to be an important client?” Nobody knew. They literally couldn’t answer it, or they wouldn’t answer it. Eventually, I said, “If we’re in the top 10 percent of your customers, we warrant this or that. If you’re willing to commit more and pay more in absolute terms, your basis points actually come down, and you ought to get a differentiated service.”

When I moved down here to take the TRS job, I’d always had a lot of collaboration in prior roles with one of the big global investment banks. After being here in Austin for a month, I received a phone call from that bank’s CEO, asking how things were going. I said that in my first month I hadn’t received a single phone call or email from his firm. He said, “What? I’m coming down there personally.” A month later, he came for a visit, we had lunch, and he was very receptive to feedback, saying, “Tell me what we can do to improve.” I told him, we drove back from lunch, and I left him in his car. TRS was in a four-story building at that time. By the time I took the elevator up four stories and got out—no more than two minutes—I had five urgent messages from people at this firm all over the world. When you’re working in a collaborative and engaged way with people who care about each other and trying to improve themselves through collaboration, then you can get an amazing result. So I believe in positive peer pressure.

McKinsey: But even while collaborating, you’re negotiating with your partners at times. How do you think about pricing, particularly in alternatives?

Britt Harris: Anytime you go into a negotiation, you’re seeking alignment, and you’re seeking what is fair and just. I stay on that point until the other side can show me something that is in fact fair and just. That’s market based: “We looked at the market, we looked at you, we looked at us, we looked at what we’re doing together. This is our best shot at what’s fair and just.” It doesn’t always happen in investing. The hedge-fund community has produced net results that are not fair and just, over the past ten years. We can give them the benefit of the doubt: they actually thought it would be fair and just, because they thought their returns were going to be a lot higher, so it wouldn’t be an issue. Hedge funds produced, say, 5 percent gross in recent years. But if our returns from them were 3 percent or 2 percent or 1 percent, then I say, “Wait a minute—this is not fair and just. We don’t give you money so that when you make a little return, you keep most of it.” They fooled the whole industry by saying that when you’re in a low-return environment, alpha is more important, so therefore it’s OK if we keep more of it. I disagree. When returns are lower on a gross basis, the customer needs more of that, not less of it. So we said to our hedge funds, “Under no circumstances should we receive less than 70 percent of the gross alpha.” You have to think through the flaws in the current model. The big flaw in the current model, where we can help them out, is that we can actually pay for outperformance in a down market.

McKinsey: You have also innovated in considering performance across mandates.

Britt Harris: That’s right. We believe in paying at the bottom line. This may be the part of the Texas model that is the most differentiated and perhaps the least achievable for others, because we did it first, at a time when the GPs were receptive. We weren’t nine years into an economic expansion. There are certain expectations for research and coinvestment and collaboration and all those things, but our partners are paid at the bottom line.

McKinsey: What are the operational implications of this approach?

Britt Harris: It gives GPs a greater ability to add value. The big four asset classes are private equity, real estate, energy, and credit. GPs can have a neutral position in each one, but also a range. If credit suddenly becomes unattractive and energy becomes really attractive, you don’t have to come back to us for approval. The Texas model also requires that GPs assign people to the strategic relationship. When those people wake up in the morning and they have to think about all their customers, the face that should come to mind is the face of the Texas person because we are their favorite customer—not because we’re pushovers, but because we’re collaborators, because we have a commitment to them, we know how they operate, we’ve been transparent, and we have a personal relationship.

McKinsey: In illiquids, TRS ended up developing a strategic partnership with two GPs. How would the dynamic have been different in your view if you had decided to partner with one GP rather than two?

Britt Harris: I don’t know. I would never do it that way, because I believe in positive peer pressure and some diversification. What made TRS different was its ability and willingness to give what was then a $3 billion account. If we had decided to write six $500 million checks instead, we would have just given up much of our unique competitive advantage.

McKinsey: In building these special partnerships with multi-asset global managers, how much depends simply on being large enough to get their attention?

Britt Harris: There are big funds and smaller funds, but you have to remember, even $30 billion or $40 billion is still a monster fund. When you talk about these managers with multi-asset-class platforms, the Texas model is not either-or. The strategic partnerships at TRS were 10 percent of the fund. That positive peer pressure is always a good thing.

McKinsey: Investment organizations depend on attracting great people. What do you look for?

Britt Harris: If you want to win the game, it’s the plan plus the people. You have to attract A players. In my view, they have a few consistent features.

One, high character; two, high intelligence; three, they’re fully engaged in everything they do; four, team player; and five, willing to take individual responsibility. You put those kinds of people in the right kind of structure and give them support, and they’re going to do amazing things. But if they’re not those kinds of people, it doesn’t matter what structure you put them into. The most dangerous person you can hire is a really smart person with really low character. You have to pass through character and integrity first; you have to be for the fund before you’re for yourself. And that takes a certain type of person and a certain type of culture.

McKinsey: You didn’t mention a person’s experience. You have a strong reputation as a talent developer. Does that suggest prior experience is secondary for you?

Britt Harris: Experience is important. But most people have one year of experience 20 times, not 20 years of experience. After a person graduates from school, there’s a lot of low-hanging fruit for growth and development. But then you get to 35 or 40, and you’ve run a discount model 1,000 times, or you’ve done 2,000 due-diligence models. Does that represent growth? I’m not against experience. If you can find people who actually have 20 years of experience and those characteristics I mentioned, they are valuable. If the person has experience but doesn’t have those characteristics, it’s not going to work.

McKinsey: Many public funds struggle with employee churn. When you talk to any of the big asset managers who form strategic relationships with public funds, this is among their top worries in building a structure like this—how much continuity will we have? How do you create that over time?

Britt Harris: People say that you can’t attract A players to a public fund, but you absolutely can. You do have to take care of compensation first. You don’t need Wall Street–level compensation, but you at least have to make compensation a nonissue. You need the right culture that attracts the right people for the right purpose. And you need the right agency system. People should want desperately to come to a fund like UTIMCO, and they should want to stay here, because we manage a lot of money for a really important purpose. When you come, then you’re working with people that you respect and admire, in a culture that is high integrity and well respected around the world. And you can work with a $40 billion or a $140 billion fund, and get well paid. That’s heaven on earth. We think that we are in the most competitive position possible.

McKinsey: What sort of culture attracts the right people?

Britt Harris: In New York City, people describe their hours as terrible, 24/7. They complain about it, but they are also proud, as if only they could do this work. I was in New York City for a long time, and I bought into this for too much of my life. Then I went to TRS, and I asked people, “What kind of culture would you like to have?” And the answer was, “We want a lot of work–life balance.” That was the number-one thing. My reaction to that was: “Me too!” I’m married, I have kids, I have lots of interests. That said, I’m not willing to retire and say at my farewell address, “Thank you for the great work–life balance I had. Sorry I underperformed and cost you billions of dollars, but it was good for me.” A high-character person is not willing to make that trade. But I’m also not willing to give up my work–life balance.

That presents a problem. Our competitors say they’re working 24/7 and have given up all work–life balance to compete against us. If you’re going to work 8 to 5, competing against somebody who’s working 24/7, and you think you’re going to outperform them, then you’re either very naive or very arrogant. So I started thinking about the 24/7 model. Why is it 24/7? Is it that the work is so hard, so different, and there’s so much of it that it takes all day and night to accomplish? And there are only five people in the whole world who can do it? That’s absurd. It’s a brute-force model. The reason they work so long is that they do things by brute force. The Texas model is to do things with your personal genius—that part of your personality and intelligence that is especially advanced. When our people sit down and apply themselves in their area of personal genius, combined with a greater purpose, we create a culture in which people can succeed.

McKinsey: How do you identify a person’s area of personal genius?

Britt Harris: There are all kinds of work that each person can do well. First, you have to realize you actually have a personal genius. The thing that people know the least about is themselves. So we do a lot of work on who you are and where you really thrive. For me, my personal genius is in administration, in teaching, and in giving.

McKinsey: What then are the highest priorities for other sorts of personal genius to surround yourself with?

Britt Harris: I have to surround myself with people who are strong in areas where I am not, whom I trust. The Texas model is in part about diversity of thinking, and diversity of thinking comes from knowing what your personal genius is, and what your perspective is. That helps you work on your strengths.

It’s also about working on your constraints, which is just as important. You alleviate your constraints by understanding what they are, and you have to learn how to overcome them. People who maximize their strengths and alleviate their constraints get to their personal genius much faster, and much more effectively. It usually takes a long time for people to accept that this is important. Those who do accept it are the fastest to learn and the first to succeed.

McKinsey: Many institutional investors are thinking about collaboration not only with external partners but also within their organization, among teams. What works well in that regard?

Britt Harris: Internally, you break down silos with compensation and with culture. Everybody should have a significant component of their compensation based on the total fund results. The higher up you go in the fund, the larger that component should be. It should be crystal clear; 80 percent should be quantitative. But getting compensation right is only part of it; you also need to get the culture right so that people realize they have to collaborate. Left to themselves, many people unfortunately tend not to collaborate, so it has to be led from the top. At many large funds, I regret to say that there is a gaping hole in the rank and file’s ability to articulate their culture. Culture, compensation, leadership, and agency structure have to all coalesce to break down these barriers. It takes time.